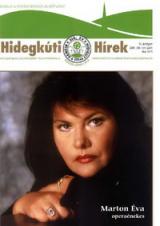

The Kossuth Prize-winner, world famous soprano, Eva Marton had many tremendous successes both in Hungary and in the great international opera houses. Beside her degree as an opera singer, which she received in the Franz Liszt Academy of Music, she is a voice teacher, too. She is a Kammersängerin and a Lifetime Honorary Member of the Vienna Staatsoper, she got “The Prize for Hungary’s Reputation” and the Bartók-Pásztory Prize.

In the atelier of Ferenc Töreky you can hear music all day long. Lights and colors play and gleam in the parturient pictures, while you can hear complete operas and orchestral works. These are inspired moments. He is inspired by illustrious works of music. Who know him, they aren’t surprised. In the spring he listened to Janáček’sJenůfa with Eva Marton. The diva, when she entered the atelier, hasn’t already been surprised, why we call her to Pesthidegkút. The outside world didn’t exist any more for us at the meeting of the two artists: they talked about fine arts and music. The time was running so fast. We asked Eva Marton to tell us, how her talent has determined her career. Who helped her in her career? What could be the way of those young people today, who would like to live complete life?

Eva Marton:

There are some born talents, who outgrow in very special places, like a flower in the desert. I could compare myself to something like this. There was nobody in my own milieu, who could lead me to this profession. My mother and my father raised three children in dignity and in faith, but they didn’t direct my career. I have never heard: “My daughter, sit to the piano”, we didn’t have any piano. I had to fight for my every ambition – that was my motive power.

Total strangers recognized my talent

I had a great fortune because of who saw the gleaming fire in my eyes, they passed me from hand to hand. It’s a great pleasure for me that I could meet with them just in the right moment, when they impressed me and they swung me to the right direction. I’m very grateful to my first singing teacher in the primary school, who graduated in the Music Academy. I was brave, I didn’t fear the people. I didn’t have to been asked: “My dear Eva, sing, please!” Eva sang. My heart was always full with music. My first singing teacher saw into my soul and after she ascertained that I have a voice, she sent me to the music school of Mester Street. The headmistress of the school, Kató Bíró was one of the last students of Béla Bartók in Hungary. How I could get to her? This is the greatest wonder! Using the flower-image, a flower outgrows somewhere, it gets liquids and the required alimentary substances and it starts to grow…

I have always known I would like to be an opera singer

The music was the only sure point in my life. As a teenager I read the world literature. I joined the library, then I got my parents to join, so in every weak I carried home twelve books and I read everything, what I could. Is it a self-instruction? Yes, it’s. Well, at that time we were totally different than who play in computer and get everything ready nowadays. They don’t have to fight and they don’t have to know even reading, because the information is on the screen. It’s very good but only in such cases when it doesn’t kill the creativity.

I was admitted to the Music Academy. I knew, never again in my life I get such a six years, when I can deal with only myself and

I have to gather all information and all knowledge.

I went to Italian lessons alone from our class. Seven students started in our class, but after the first year only two remained. In the Franz Liszt Academy of Music an excellent man and tenor, Endre Rösler helped me. After his death Dr. Jenő Sipos was my professor through three and a half years. I enjoyed the every pleasure of the artist-education.

I graduated in 1968 with excellent results. In spite of this I was the sole who wasn’t engaged by the Hungarian State Opera. Then, after all, I managed to get into there with a ministerial scholarship. My first role was the Player Queen in Sándor Szokolay’s Hamlet. It’s a speaking role, I didn’t sing in it. This isn’t a dream for a beginner soprano! In this month, in the end of September I sang Queen of Shemakma in Rimsky-Korsakov’s The Golden Cockerel (Le coq d’or) in the second cast. I got many roles, but only that kind of roles, where there was a little place in the program, which was filled with me. Once I asked what fate would be planned for me. The then director, Miklós Lukács opened a little, checked booklet at the name of Eva Marton. My heart palpitated, when I looked into it from the other side of the table and both pages were empty. I thought to myself: Oops! These don’t plan anything with me! So I go away.

I ought to have waited for seventeen dramatic sopranos that I could take place after them.

For me every negative thing becomes positive

One of these sopranos told me: “Why are you a nuisance? You are young, you are talented, you have a chance, go west!” I took her at her word. In the 1971-72 season a new edict was made, which stood me in good stead: “I wouldn’t like to extend my contract, please!” Even then Christoph von Dohnányi gave a concert in Budapest. I went to audition to him. Unsurprisingly I found myself Frankfurt am Main. I learnt and sung on end. In April 1973 I sung Toscain the Wiener Staatsoper, as a guest singer. That autumn I portrayed Eugene Onegin’s Tatiana there. Between these I sang in Verdi’s Attila in the Open Air Theater of Margaret Island (Budapest) with Lamberto Gardelli. It was wonderful!

I could narrate and teach very much.

Teaching? If somebody comes to me and I see the sacred flame in his or her eyes, I give a chance for him or her. That is another question if he or she can doesn’t make the best of the opportunity. It is one of those things, that I listen him or her, he or she is very fine, I help him or her, then he or she underachieves in the preliminary. That failure is his or her failure, I don’t suffer from it. For me it was a great fortune that I have never been frightened. I felt freedom when I sang in the Metropolitan or in La Scala. I have always decided my will. Anybody could interfere in anything, but I don’t hear it. It’s like when you go in a dark tunnel and there is a great brightness in the end.

The opera is the most complex art form

It isn’t normal that we sing on the stage and despite this, it impresses everybody. The singing is the heightening state of the soul. For example there was a Lohengrin-premier last year (in Budapest, in Erkel Theater). In 2004. When there is so much awfulness in the world, where are the heroes? Where is a mythical person, where are the redeemers, where is Lohengrin? This opera, which was played in modern direction, shows our age: there were elections on the stage, we run with elective cards, there was a peaceful revolution, when the people went into the parliament… Let’s imagine, Lohengrin flies away by a jumbo jet. Lohengrin might have been the hero. Instead of this the director chooses the homeless bum, clothes him, gives an attaché-case to his hands and says to the audience: “Here it is, if you need this”… A work couldn’t be more current!

- Is it anachronistic that there are classical directions in the Hungarian State Opera?

If I were the director of the State Opera, I would tell: let’s play like this and let’s play like that.

For example I would bring out Le nozze di Figaro or Don Giovanni, but I would present a modern work of a talented, young composer. Then I would call the audience together and I would ask, what they get, what was good according to their opinion. Two years ago I competed for the directorship of the Hungarian State Opera. When the new director was appointed, I congratulated him among the firsts. I was glad that many ideas, what I drafted in my application, have been realized since then. It’s a great pleasure for me that Janáček’s Jenůfa and Wagner’s Lohengrinhave been billed by the Hungarian State Opera. But many operas are missing from the repertory. For example: Where are the great operas of R. Strauss? Where are the pre-classical works?

If there is a great talent, we have to help him or her very much.

I put a question to myself: maybe we aren’t so strong that these young children can’t really grow up stand by us, in that way, that they should.

I always start my master classes with that: “what I have reached, you can reach it, too.” It will be successful if we endeavor, if we have great diligence, if we wish. You can’t get anything without work. I show my own example. It’s strange but I have to say that this is a disadvantage for us, that the world has opened with our membership in the European Union and – at all – with the fall of the iron curtain. I experience in the international singing competitions that the “market” is overrun by singers from East and Far East, and at the same time the Hungarians aren’t weighed in the balance. The Hungarians were always famous for having numerous ideas.

But the art isn’t an idea, but a process, a permanent preparation, a practice, a work and – sometimes – a failure, too.

The people don’t want to accept the latter as a natural thing. Why do we fear of failure? Not only the success promotes you, but also that, if you can learn very much from the failures, too.

Eva Marton sings the role of Kostelnička in Jenůfa in the Hungarian State Opera on 9, 12 and 16 October. In the end of October she has a public meeting and a master class in Szeged. In November she has a recital-tour in Spain. In December she portrays the title role in the Elektra-premier of the Deutsche Oper am Rhein in Düsseldorf.

Katalin Erdősi

(Hidegkúti Hírek. Vol. XV., 2004 October-November p. 8-9.)